From FEA to firmware: why your next digital twin needs machine learning

For decades, simulation engineers have been perfecting the craft of physics-based modeling. We build detailed Finite Element (FEA) models, calibrate them against experimental data, and use them to predict how complex systems behave. This approach has been the backbone of modern engineering, helping us design everything from safer vehicles to more efficient power electronics.

But here’s the catch: the real world rarely follows the neat rules of our carefully controlled simulations. Out there, conditions change all the time, often in unpredictable ways.

At Newtwen, we don’t think the solution is to abandon physics-based models. Instead, we believe in enhancing them. By combining them with machine learning, we can create a new type of “intelligent” digital twin — one that’s not only accurate during design but also robust and adaptive throughout the entire lifecycle of a product. This is at the heart of what many call Scientific Machine Learning (SciML).

The limits of purely physics-based models

Take a common challenge: managing the thermal behavior of an electronic board inside an EV powertrain. The natural first step for an engineer is to build a high-fidelity thermal model.

The latter means constructing a detailed digital replica grounded in physics. Engineers typically start with the 3D CAD geometry and use methods like Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to perform a spatial discretization of the entire topology. This process divides the complex physical structure into a fine mesh containing thousands or millions of smaller, simpler elements. By numerically solving the governing partial differential equations for heat transfer across this mesh, the model can precisely simulate complex thermal phenomena—from heat generation in a semiconductor to its conduction through the PCB and its convection into a cooling fluid.

This process yields an incredibly accurate simulation, but one that is also computationally intensive, making it unsuitable for real-time applications.

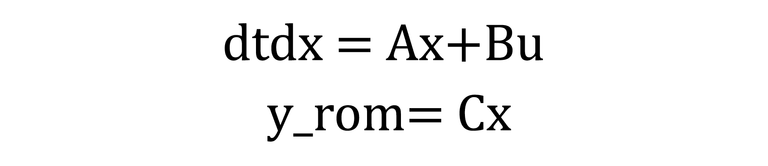

To make simulations faster, engineers often use Model Order Reduction to create a Reduced Order Model (ROM), a simplified but efficient version of the original FEA model. Calibrated with experimental data to ensure it accurately reflects the underlying heat diffusion physics. Mathematically, a linear time-invariant (LTI) ROM can be represented in a state-space form:

Where:

- x is the state vector (e.g., temperatures at various nodes).

- u is the input vector (e.g., heat sources).

- yrom is the ROM's output vector (e.g., estimated temperatures at sensor locations).

- A, B, and C are the state-space matrices derived from the discretized thermal physics.

In theory, it works beautifully. In practice? Only as long as the system conditions stay the same as those assumed during calibration. Once something shifts — say, ambient cooling changes unexpectedly — the predictions start drifting away from reality.

Why? Because the ROM’s matrices (A, B, and C) are fixed. They don’t “know” that the environment has changed. The model will continue to provide estimates based on its original assumptions, leading to a growing divergence from reality, and accuracy will quickly fall apart.

One solution is to create a library of ROMs for every conceivable operating condition. But this is cumbersome and impractical to scale. Another classic possibility is to leverage observer theory from control engineering. This reframes the challenge as an observer design problem. Useful, but as we’ll see, it has its own limitations.

A control-theoretic perspective on the problem

From a systems perspective, this is indeed an observer design problem under uncertainty. Traditional linear observers, such as adaptive, robust, or multiple-model, all rely on the assumption that the system structure is fully known.

The fundamental challenge is that classical linear observers assume perfect knowledge of system dynamics.

But in reality, we’re dealing with:

- Simplified physics knowledge (captured in the ROM)

- Unknown, time-varying disturbances (like changing boundary conditions)

- Limited sensor data (only a handful of temperature readings)

And that’s exactly where classical approaches struggle. They can’t fully handle these unknowns. Which is why a data-driven correction method doesn’t just look like an alternative, but it’s often a mathematically superior solution

The hybrid solution: physics + data-driven correction

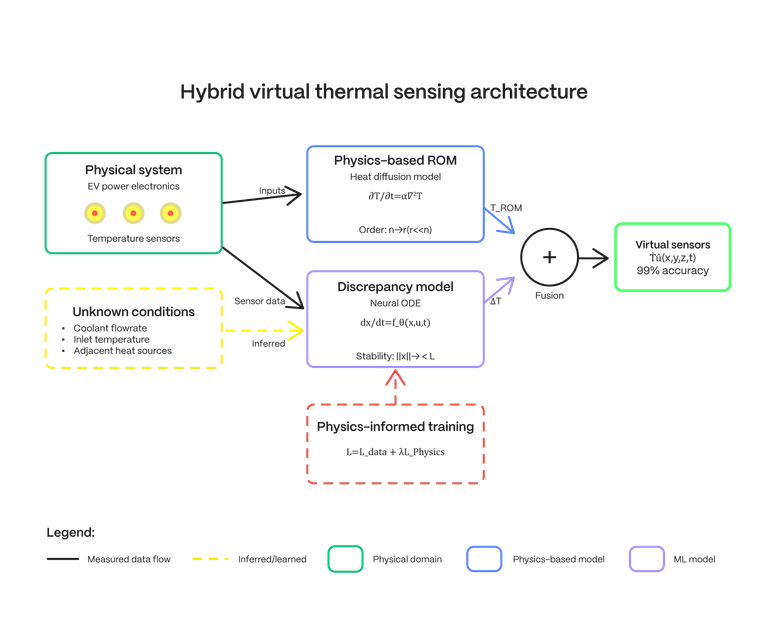

This is where Scientific Machine Learning makes a real difference. Instead of replacing physics-based models, we complement them.

At Newtwen, we call this extra layer the discrepancy model.

It’s a small, efficient neural network that runs alongside the ROM. Its job is simple but critical: to learn the gap between what the ROM predicts and what sensors in the real system are actually measuring.

Our ROM provides: ŷ_rom = Cx̂ Reality gives us: y_measured = Cx + v(t)

The discrepancy function δ(t) = y_measured - ŷ_rom contains information about both the unmeasured disturbances and model uncertainties.

Key insight: If δ(t) exhibits learnable patterns (which it typically does, since physical disturbances often follow predictable dynamics), we can construct a nonlinear estimator to predict this discrepancy in real-time.

This transforms our problem from:

"How do we perfectly model unknown disturbances?" (impossible)

To:

"How do we learn the mapping from observable quantities to discrepancy patterns?" (tractable)

Here’s how it works in practice:

- Physics-Based Estimation: The calibrated ROM provides real-time thermal estimates grounded in first principles physics.

- Sensor Feedback: A few sensors on the hardware (often already there for functional safety) provide actual temperature readings.

- Discrepancy Learning: The neural network looks at both the ROM’s predictions and the sensor data. It learns the complex, non-linear patterns that the ROM cannot capture, essentially inferring the impact of the unmeasured boundary conditions and the fingerprint of eventual disturbances.

- Real-Time Correction: The network then adds a correction factor to the ROM output, keeping it aligned with reality.

The result is a hybrid model that combines the best of both worlds:

- The ROM guarantees a physically grounded foundation. It ensures the model's predictions are always consistent with the laws of heat transfer.

- The Discrepancy Model adapts to changing conditions and captures the messy, nonlinear effects the ROM simply cannot.

The result? A virtual sensing framework that can achieve upwards of 99% accuracy, dynamically adjusting as the system operates. Instead of a static simulation, you get a living, learning digital twin.

Making it safe at the edge: stability-guaranteed neural ODEs

Accuracy alone isn’t enough when we’re talking about safety-critical applications like EVs. Stability is just as important. We can’t deploy a model that behaves unpredictably in real time.

Ideally, our neural network should be capable of adapting to rapid changes, with the ability to process nonlinear dynamics. And one more important thing is that we want to ensure that the hidden state of the network remains bound in time. Bounded hidden states ensure numerical stability and prevent gradient pathologies. When states grow unbounded, activations saturate, gradients vanish, and the network loses its ability to adapt to new information, essentially becoming 'frozen' rather than genuinely forgetting.

To prevent this, we use a special type of recurrent neural network built on Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs) with contractive dynamics. The design includes a natural negative feedback loop that keeps the internal states bounded. In plain terms, the network stays numerically stable, no matter how long it runs.

Without getting lost in mathematics, the key takeaway is that, with recent advancements in the AI field combined with our latest research on the topic, we can guarantee that these neural models remain stable, reliable, and mathematically verifiable.

This moves the conversation about machine learning in engineering away from a "black box" perspective and towards a framework of verifiable, trustworthy engineering tools.

From design tool to operational asset

For simulation engineers, the message is clear: your physics expertise is more valuable than ever. SciML isn’t here to replace it. It’s here to amplify it.

By adopting this hybrid approach, you can:

- Extend the lifecycle: Transform design-phase models into operational assets for monitoring, predictive maintenance, and control.

- Boost accuracy: Build digital twins that stay robust in the face of real-world uncertainty.

- Unlock virtual sensing: Estimate variables that are too expensive or impossible to measure directly, enabling smarter sensing and control.

At Newtwen, our software Twin Fabrica is designed for exactly this: turning ROMs and discrepancy networks into live digital twins running at the edge.

The future of engineering isn’t physics versus machine learning. It’s the fusion of both. It’s time to equip our models with the ability not just to explain physics, but to learn and adapt to the ever-changing world around us.